Traversing coordinate systems

Imagine you’ve got a 3D model in a scene, a virtual camera is viewing it. But how do the vertices of the model ultimately end up on the 2D screen? We’ll walk through the various coordinate system transformations involved in that in this section, with lots of diagrams and minimal maths!

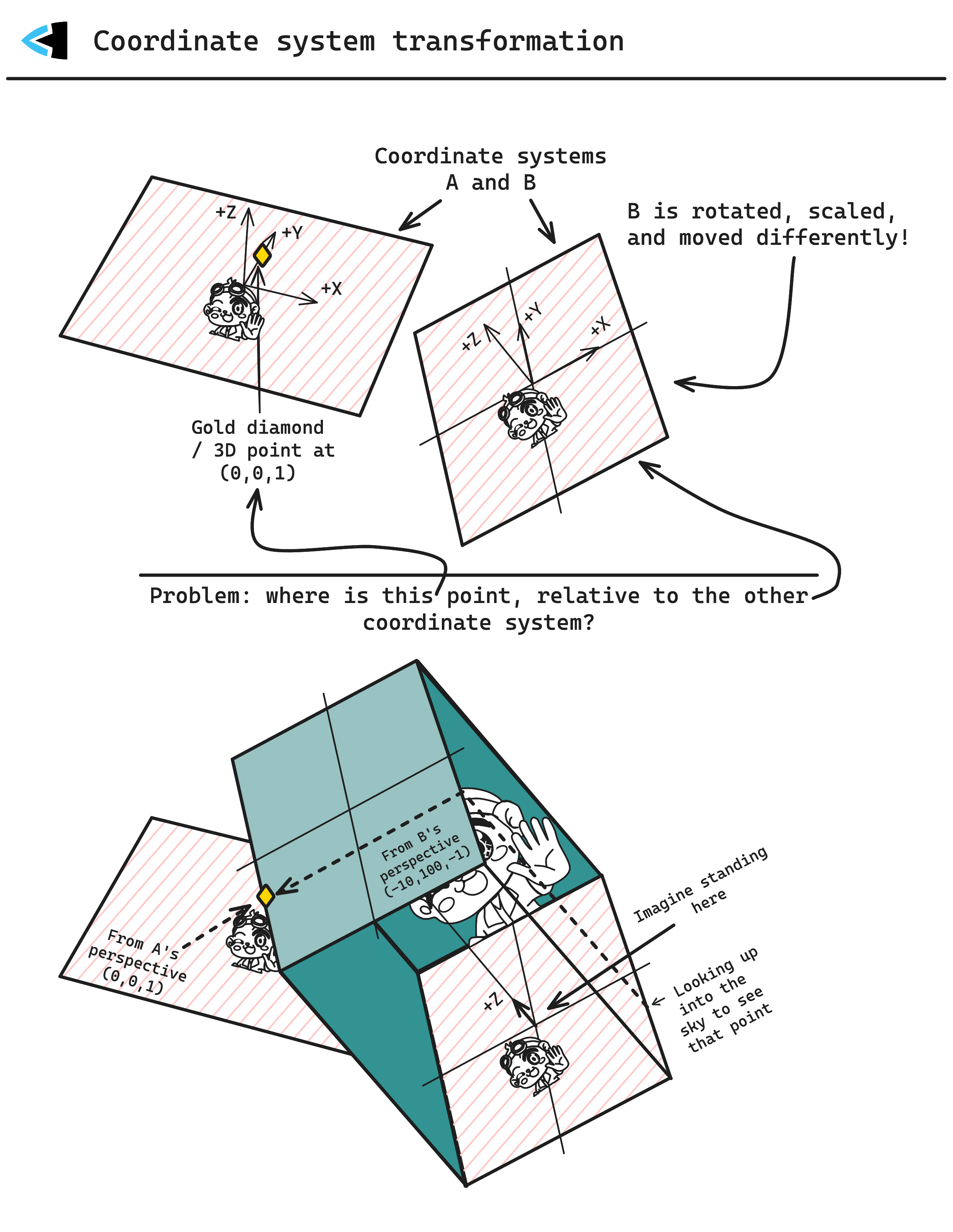

Cartesian coordinate system transformations

First we need to know what a coordinate system transformation is. Imagine a typical 3D grid like you’d find in a 3D model editor, such as Blender. That’s a 3D cartesian coordinate system - the linear axis in X, Y, and Z dimensions.

Pick any point on that grid. Then imagine a second grid / coordinate system, overlayed exactly with the other one. But this one you can move, rotate, scale, etc.! As you do, the point you chose on the first grid remains in the same location.. but in the 2nd grid its location changes depending on how you move/rotate/scale the grid!

The fact that we can take a point anywhere in the first grid, and determine where it would be in the 2nd grid which is moved/rotated/scaled, is a coordinate system transformation and is what a matrix transformation does. Keep this in mind as you think about the transformations we describe later.

Model -> World space

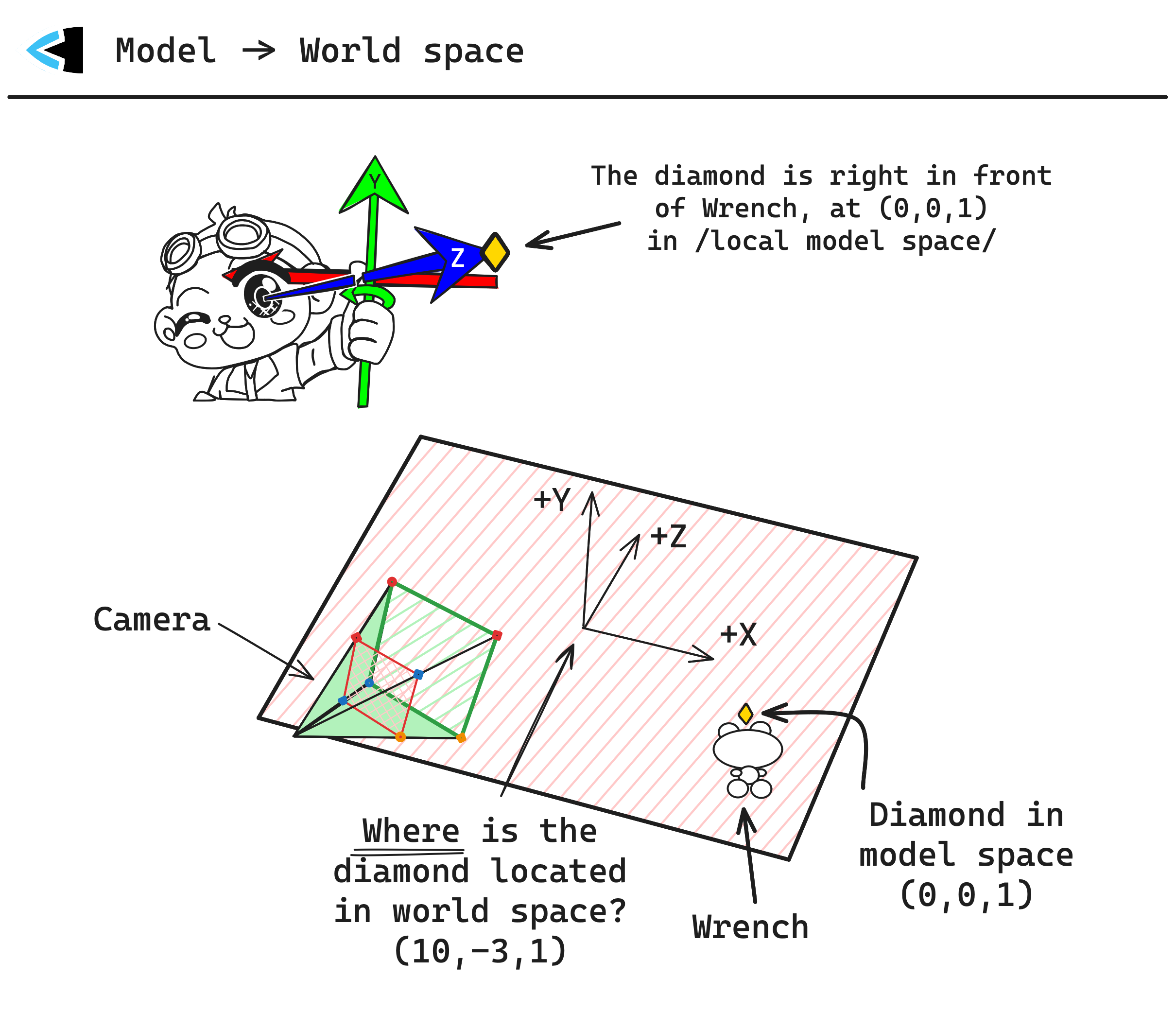

Now that we understand what a coordinate system transformation is, we can begin talking about the first one we need to perform: Model -> World space. Imagine a vertex on a 3D model: the point of a diamond floating in front of a monkey

This vertex is said to be in the local space of the model, or just ‘model space’ for short. We get to decide what unit of measurement is used, as long as we’re consistent everywhere - so let’s say our unit is meters. The position of this vertex at the tip of the monkey’s hand is (0, 0, 1) in model space: ‘one meter in front’ of the monkey, from the perspective of the monkey. It doesn’t matter where the monkey is located in the world, that vertex is always at (0, 0, 1) in model space because it is from the perspective of the monkey.

The Model matrix describes how to transform a point in model space into world space, so that we can say ’the monkey’s finger tip’ is at a specific point in the world, rather than being relative to the monkey’s location/rotation/scale/etc.

World -> View space

Next up, we need to convert from world space into view space. Just like how model space is relative to the model, view space is relative to the viewer (i.e. the virtual camera of the scene) - this lets us say “this vertex in the 3D world is at (x, y, z) relative to the camera/viewer.”

This is like the opposite of what we just did above: going from Wrench’s local model space to world space. Instead, we’re going from world space to the camera’s local space.

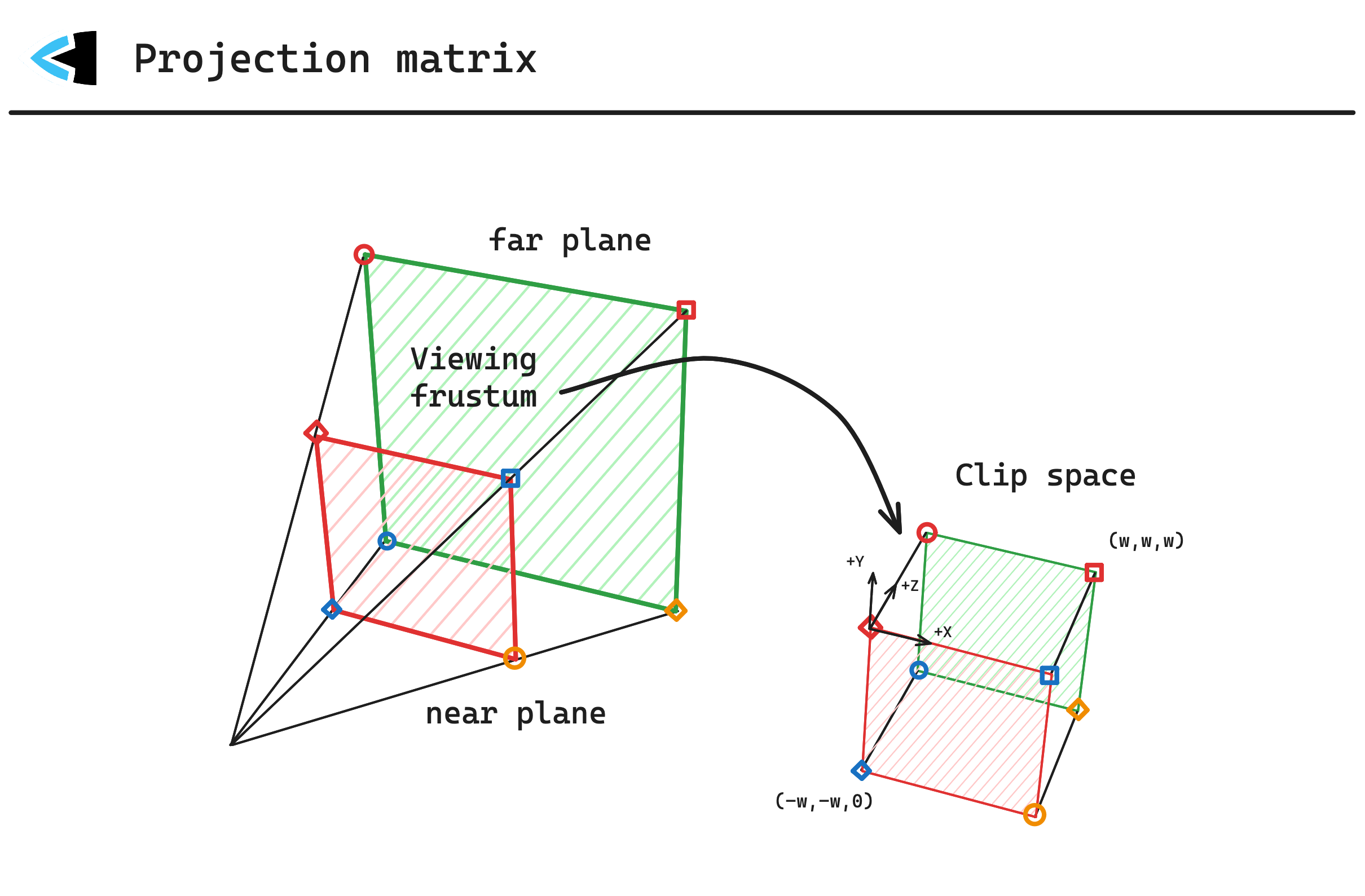

View -> Clip space

Now that we know where the point is in view space / relative to the camera, we need to transform the vertex into clip space. A projection matrix is used for this, taking 3D points relative to the viewer, and transforming them into a normalized clip space bounding box.

Notice how the view frustum above represents a sort of virtual camera lens, with the far plane being much larger than the near plane. The shape of the view frustum is what makes our geometry look like it is in 3D space, objects further away from will appear smaller and objects closer to the camera will appear larger. For 2D games, an orthographic projection matrix is used instead of the ‘warped’ perspective projection matrix shown above.

Also note that the view frustum is where we take into account the aspect ratio and field-of-view. For 2D games, the orthographic projection matrix often e.g. determine how many world-space units map to a single fragment/pixel on screen.

The clip space volume / bounding box on the right is a concept defined by the underlying graphics APIs and hardware. When a vertex shader runs on every vertex of a 2D/3D model, its goal is to output the position of the vertex in clip space. Unlike our other 3D coordinate spaces so far, clip space is a 4D homegenous space - also known as a ’projective space’.

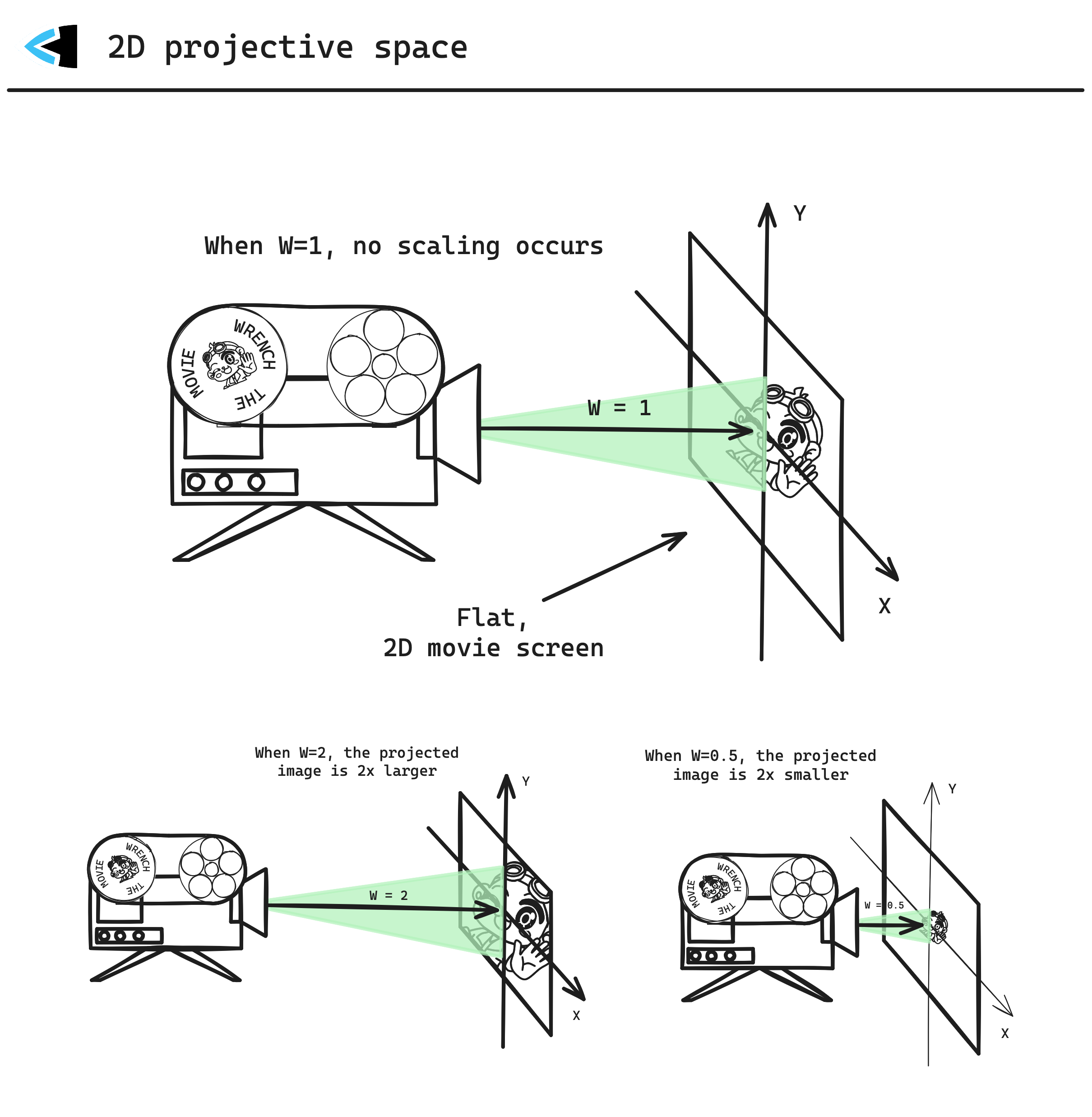

Projective geometry

In all our other 3D coordinate systems so far, we’ve been thinking in terms of Euclidean geometry with [x, y, z] points. But in clip space, we need to think in terms of Projective geometry instead with [x, y, z, w], where 𝑊 acts basically as a scaling transformation for the 3D coordinate - which will be used in our next transformation.

The above diagram shows 2D projective space, with [x, y, 𝑊] - but clip space on GPUs is in 3D projective space, with [x, y, z, 𝑊] components. It’s hard to visualize adding another dimension to the diagram above (a projector which exists in 4D, and projects onto 3D space) - so you’ll have to use your imagination - but how 𝑊 works remains: as it increases, the coordinate [x, y, z] expands (scales up) and when 𝑊 decreases, the coordinate [x, y, z] shrinks (scales down). Each vertex can have its own 𝑊 value, and so each vertex effectively lives in its own unique projective clip space. The 𝑊 is basically a scaling transformation for the 3D coordinate.

Clip space continued

The vertex shader (i.e., you) are responsible for producing that four-dimensional vertex position in clip space. Vertices form primitive shapes (like triangles), and when they go beyond the bounds of that clip space volume / bounding box in the diagram shown earlier, or if they intersect it, the GPU will clip them. You can literally think of a piece of paper in the shape of a triangle, then imagine using scissors to clip a portion of the triangle off!

Anything that is outside the clip space volume / bounding box, any points that do not pass the following tests, will be clipped:

- −p.𝑊 ≤ p.x ≤ p.𝑊

- −p.𝑊 ≤ p.y ≤ p.𝑊

- 0 ≤ p.z ≤ p.𝑊 (depth clipping, optional)

GPUs use the clip volume to determine what actually needs to be rendered. Fragments/pixels/vertices outside of this clip volume, anything off-screen or behind the viewer/camera, do not need to be rendered.

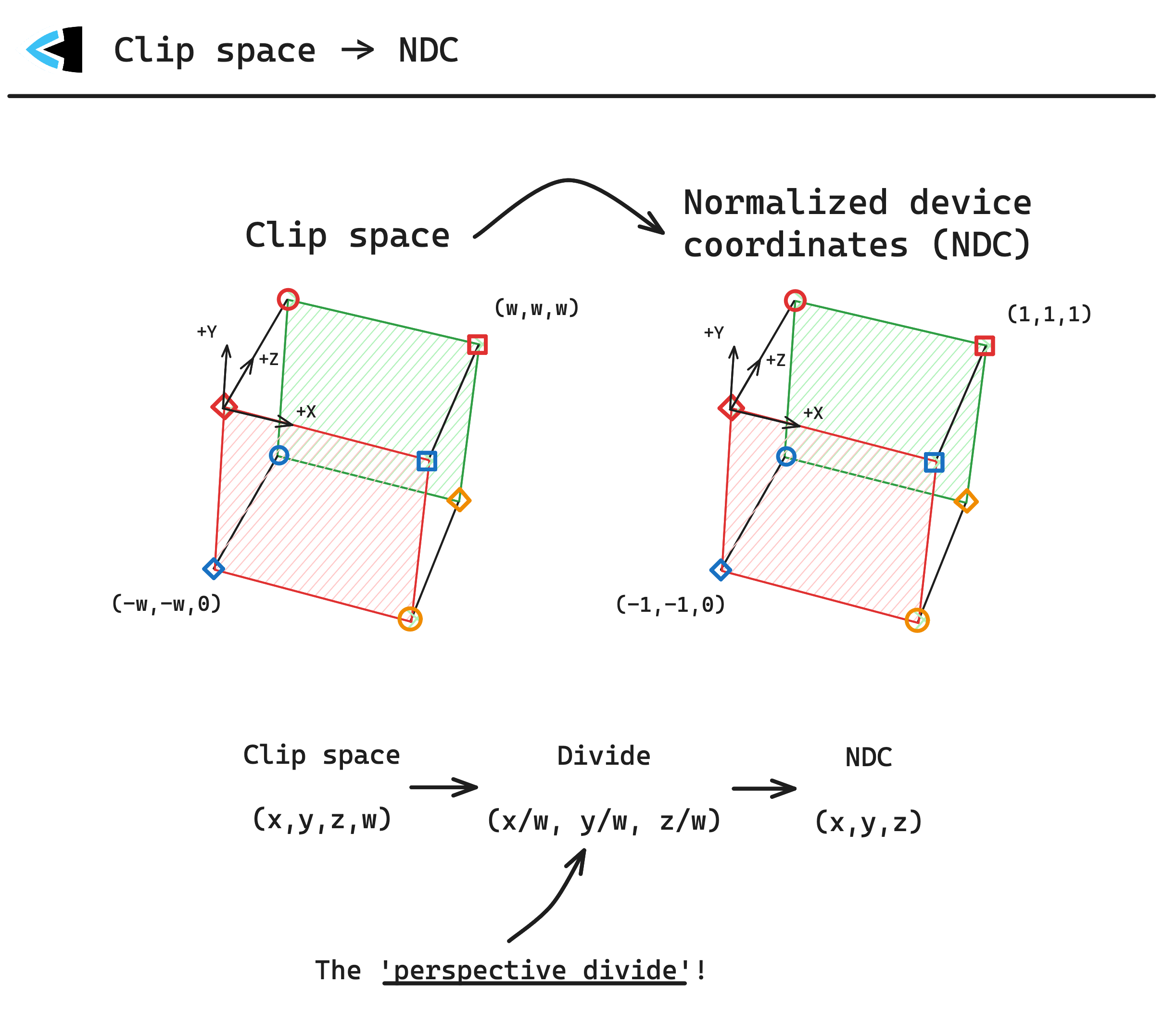

Clip space -> NDC

Finally it is time to perform the perspective divide, and get our clip-space coordinates into normalized device coordinates (NDC).

Much like clip space, NDC is a bounding box:

- -1.0 ≤ x ≤ 1.0

- -1.0 ≤ y ≤ 1.0

- 0.0 ≤ z ≤ 1.0

- The bottom-left corner is at (-1.0, -1.0, z).

To convert from clip space -> NDC, we perform the perspective divide, take the (x, y, z) components and dividing each by the 𝑊 component, this converts a 4D clip-space coordinate into 3D space once again.

Rasterization

Multiple vertices in normalized device coordinates make up primitive shapes (like triangles), which the GPU performs rasterization on, rendering to texels in the framebuffer, depth buffer, etc. This involves many other aspects we won’t go into here: multisampling, depth testing, front/back-face culling, stenciling, scissor operations, and more! It also involves running your fragment shader for each fragment that would end up in the framebuffer and, ultimately, as a pixel on the screen.

What we will explain here is how normalized device coordinates end up mapping to framebuffer space, though!

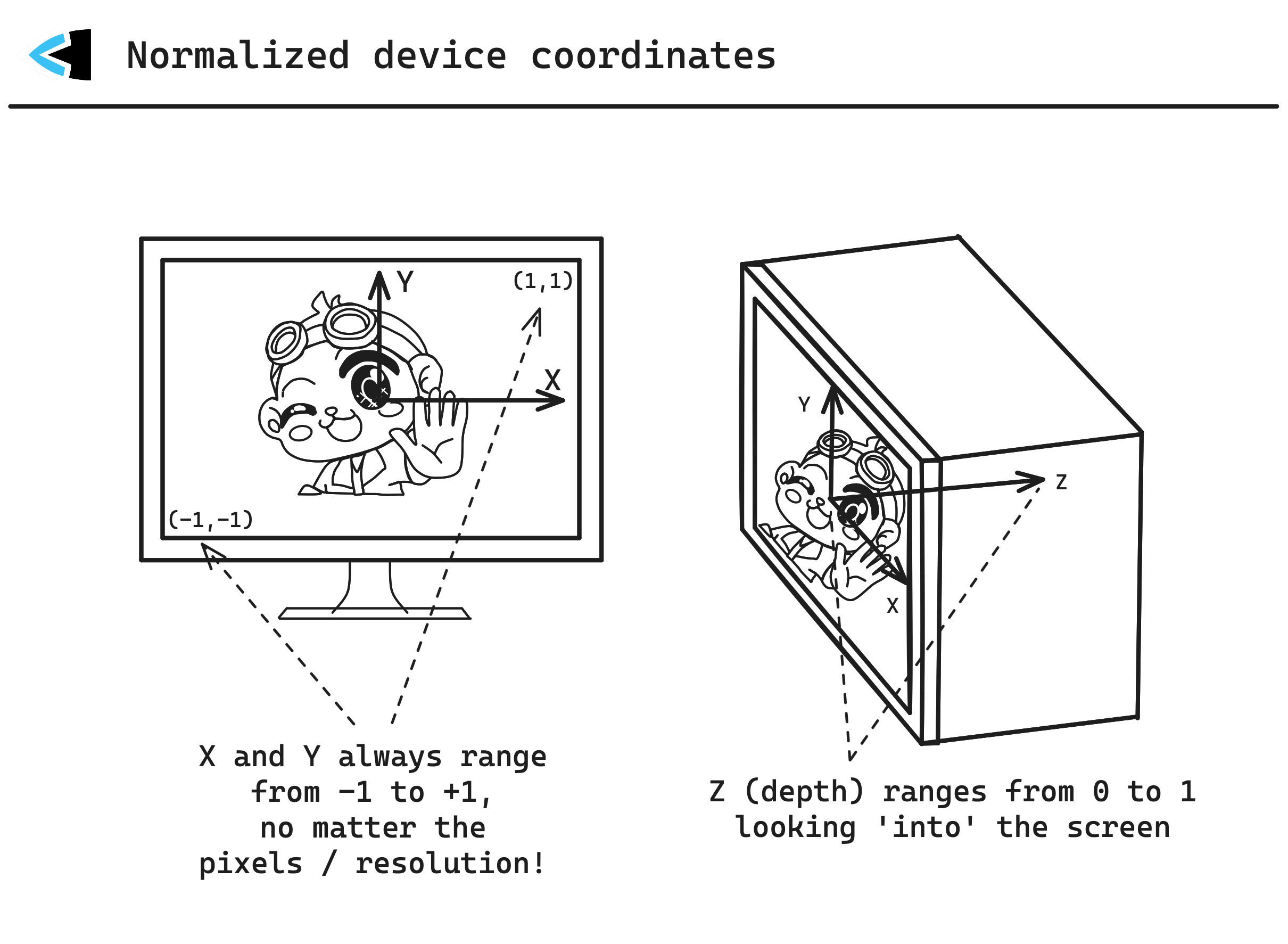

Normalized device coordinates

Here you can see how normalized device coordinates would map to e.g. a fullscreen window.

(x=0, y=0) is always the center of the framebuffer, whether it’s a window, a fullscreen application, running at any resolution - it’s always the center! (-1, -1) is always the bottom-left, and (1, 1) the top-right. The Z axis extends from z=0 (the surface of your screen) into it at z=1.

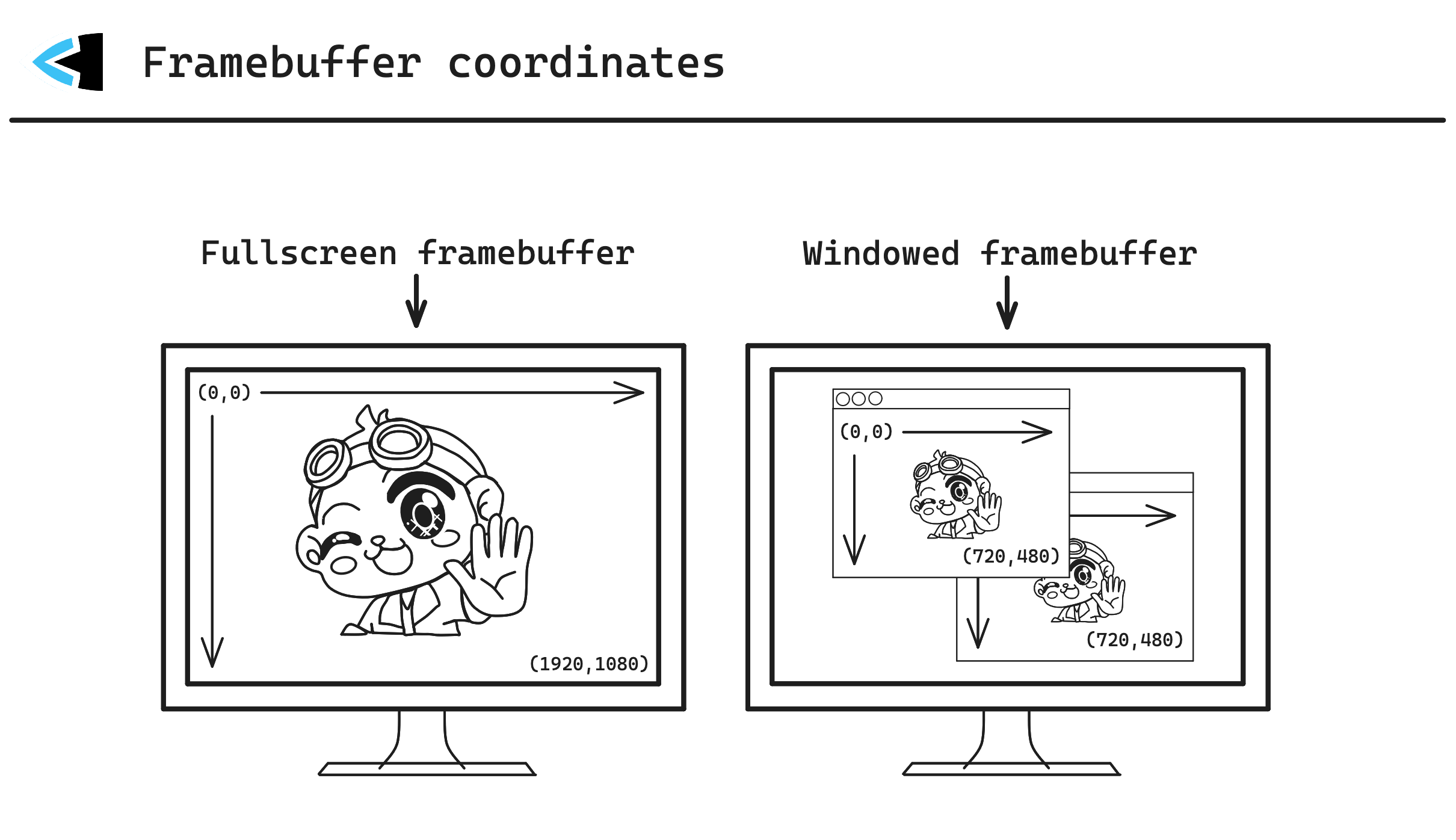

Framebuffer coordinates

It’s worth noting that framebuffer coordinates are not always the same thing as pixels. Framebuffers hold texels. As displays became higher and higher in their resolutions, OS developers decided that physical pixels on your screen and virtual pixels used to position/place things on screen, would be different concepts. Blegh!

For example.. you may create a window on your screen which is 720x480px. On a machine with an older display/monitor/OS version, that may mean you get a 720x480 resolution framebuffer, everything matches, great! But on a newer system with a HDPI display, you may find that your 720x480px window has a framebuffer resolution of twice that, at 1440x960! In this case, one virtual pixel maps to four (2x2) physical pixels on the display!

macOS, Windows, Linux, and cellphones all have this distinction today between physical and virtual pixels, with various options that affect the mapping of virtual->physical. Some platforms (e.g. Linux) even allow for fractional scaling, where e.g. a virtual pixel may be made up of say 2.1 physical pixels, so your 720px wide window might end up being 1512px wide!

The key thing here to keep in mind is just that the window resolution != framebuffer resolution, you’re always rendering pixels/texels into the framebuffer, but there’s no guarantee a pixel/texel in the framebuffer will be displayed as 1 physical pixel on the screen. You may need to convert between the two frequently.

You are now a multidimensional wizard!

You’re now capable of traversing the various coordinate systems, to 4D space and back again - or, at least, hopefully you have a clearer picture of the parts involved in getting a vertex in the 3D world to end up on the screen at the end of the day.

Donate

Donate